‘Refractive Surprise; The Big Taboo’ – ESCRS event summary

Posted on 29/09/2015

At the 2015 meeting of the European Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgeons Rayner hosted a Satellite Symposium featuring the topic of refractive surprise. The session was introduced and moderated by Prof. Rudy Nuijts, who highlighted that refractive surprise is a serious challenge in cataract and refractive surgery and requires further thought for management. The topic was presented in two presentations, from Professors Mats Lundström and James Wolffsohn, and a round table discussing interesting cases. Rudy Nuijts

In the first presentation, entitled ‘Numbers Don’t Lie’, Prof. Mats Lundström introduced the European Registry for Quality Outcomes in Cataract and Refractive Surgery (EUREQUO), of which he is Clinical Director. With the aim of improving treatment and standards of care and developing evidence-based guidelines for cataract and refractive surgeries across Europe, EUREQUO offers a web-based platform where surgeons can input their cataract and refractive surgery data manually or transfer their data through an interface.

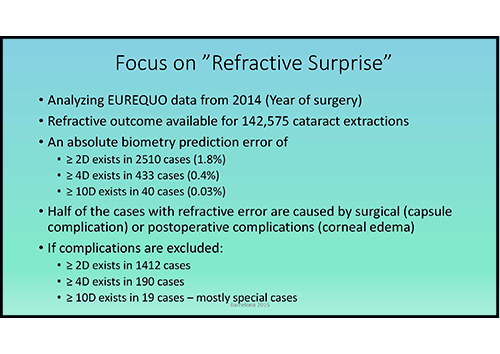

Prof. Lundström reported that more than 1.8 million cataract extractions and 35,000 refractive surgeries have been registered with the database to date. More recently, EUREQUO has introduced patient-reported outcomes as part of the database system. Prof. Lundström reported that he had analysed EUREQUO data for surgeries that took place in 2014, with refractive outcomes available for 142,575 cataract extractions. He argued that there appeared to be no clear definition of what constituted a “refractive surprise”, but he defined it according to the absolute biometry prediction error in three incremental categories at ≥ 2D, ≥ 4D and ≥10D, which were reported for the 2014 data at 1.8%, 0.4% and 0.03% respectively. Approximately half of the cases with refractive error were caused by surgical (capsule) complications or postoperative complications (corneal oedema). Prof. Lundström and colleagues conducted an analysis of the refractive error (spherical equivalent), confining the assessment to cases with errors between ±2 and ±6D, which comprised 2387 (1.7%) of the cases. If surgical and postoperative complications were excluded from this amount, only 1287 (0.9%) cases remained.

Prof. Lundström highlighted the following significantly related (by logistic regression analysis) components to this refractive outcome: poor preoperative visual acuity, patients of younger age, myopic target refraction, ocular co-morbidity (glaucoma, age-related macular degeneration, amblyopia and “other”), and surgical difficulty (previous corneal refractive surgery, corneal opacities and “other”). Providing examples of risk estimates for a biometry prediction error of ±2 to ±6D from the EUREQUO database, Prof. Lundström showed that patients with poor preoperative visual acuity (LogMAR 1.0 or more), aged below 70 years and with a target refraction of -2.0 or less had a 9.5% risk of biometry prediction error. The risk estimate for patients fitting the same profile but with the addition of glaucoma was 13.3%, with the addition of amblyopia was 17.9% and with the addition of corneal opacities was 28.6%.

In ‘Explaining the Gap between Data and Reality’, Prof. James Wolffsohn underlined the challenges of high patient expectations in terms of refractive outcomes following IOL implantation. Prof. Wolffsohn highlighted the criticality of biometry in modern cataract surgery to ensure that measurements were adhered to as precisely as possible. He also discussed various other challenges, including the use of axial length and keratometry by different formulae, and taking advantage of various surgical guidelines such as those offered by the National Health Service in the UK (where 87% of cases were within ±1D) and the Royal College of Ophthalmologists Cataract Surgery Guidelines (where 85% of cases were within ±1D and 55% were within ±0.5D).

Prof. Wolffsohn referred to Norrby’s 2008 publication on various forms of error, and how these errors could be accounted for in terms of biometry. Significantly, 35.5% of errors derived from post-operative IOL position, 17% were related to axial length, 10% to keratometry and 27% to postoperative refraction. Prof. Wolffsohn defined the components of “perfect version” to include axial length precision, but also effective lens position, which he argued was the more challenging aspect of biometry. Another component of “perfect vision” was corneal shape, according to Prof. Wolffsohn, with the use of keratometry measurements. A final component of “perfect vision” is tear film – if a patient’s tear film is distorting within placido imaging within only a few seconds, the measure of corneal power is going to be affected accordingly – this highlights the significance of the quality of tear film analysis. There are also additional findings to keep in consideration, according to Prof. Wolffsohn, including being aware of head-tilt in keratometry readings, taking advantage of using distinct refractive indices for each component and the challenges that still remain with toric IOLs.

During the subsequent Q&A session, discussions involved emphasising the significance of poor visual acuity in postoperative refractive outcomes, awareness of the disparity of measurements using different instruments when choosing the axis preoperatively and the pros and cons of digital versus manual techniques for marking.

The second portion of the symposium focused on case studies. Mr. Allon Barsam presented a case study with the Sulcoflex pseudophakic supplementary IOL. In his case, an 88-year-old woman with bilateral dense cataracts presented with preoperative best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 6/24 in the right eye and 6/10 in the left eye. The patient had approximately 2D of against-the-rule corneal astigmatism in each eye. Mr. Barsam treated the patient with bilateral phacoemulsification followed by implantation of Rayner’s T-flex aspheric toric IOL.

Postoperatively, the patient had unaided vision of 6/5 in the right eye and 6/6 in the left eye, and refraction was +0.25 and +0.50 in the right and left eyes respectively. Following surgery, the patient was left “completely miserable” because she had lost her intermediate vision. Mr. Barsam emphasised the need for surgeons to listen more closely to patients and to try to understand why patients are unhappy and attempt to address the issue. Thanks to modern technology, Mr. Barsam said, there are a myriad of options available to help turn unhappy patients into happy ones. Mr. Barsam responded to this particular patient by working with an optometrist to place the patient on a one-day trial of a soft contact lens over the left eye to meet a refractive aim of -1.50. The patient’s tear break-up time was 4 seconds and she had significant meibomian gland dysfunction, allowing Mr. Barsam to conclude that the patient was not a good candidate for laser refractive surgery. Mr. Barsam said that Rayner’s Sulcoflex pseudophakic supplementary IOL was an ideal choice for this patient, with its stable fixation in the ciliary sulcus and posterior-angulated haptics that reduced the chance of iris chafing and avoided contact with the iris. Following implantion of the Sulcoflex, the left eye refracted to -1.25, with the patient enjoying mini-monovision with restoration of intermediate vision and some reading vision.

Prof. Michael Amon presented a case entitled ‘Aspheric Sulcoflex with Multifocal IOL in the Bag’.

A 64-year-old female patient presented to Prof. Amon after having undergone uneventful phacoemulsification and implantation of a diffractive multifocal IOL in each eye. Her UCVA was 0.7 in the right eye and 0.8 in the left. Her refraction in the right and left eyes was +0.75 D (and +0.25 D Cyl/16) and +0.50 D (and +0.50 Cyl/178) respectively. The patient was unhappy and complained about difficulties in reading, distance perception and headaches. The patient’s surgeon had then performed a YAG capsulotomy. After seeing the patient, Prof. Amon decided that implanting a Sulcoflex lens would help to correct the refraction and avoid explantation of the multifocal lens. Since a multifocal lens was already implanted, it was easier to conduct calculations, where only the spherical equivalent of the patient was required. In this case, the patient needed +1.5 D in each eye. Following Sulcoflex implantation, the patient reported with a UCVA of 1.0 in both eyes and high satisfaction. Prof. Amon emphasised that the Sulcoflex presented an elegant solution for such patients.

Dr. Tiago Ferreira presented a case on ‘Posterior Keratoconus’. A 61-year-old female patient was unhappy with the visual acuity of her left eye. She had amblyopia in the left eye and cataract surgery three months prior to her visit to Dr. Ferreira. Her UDVA was 20/20 in her right eye, and 20/400 in the left. Her CDVA was 20/20 (-0.75 x 110°) in the right eye and 20/50 (+3.50 -2.75×30°) in the left. Slit-lamp biomicroscopy of the left eye revealed paracentrally localised depression of the posterior cornea with guttae on the zone of depression. Corneal tomography revealed inferior steepening with reduced pachymetry in the right eye, and on the anterior surface of the left eye, an area of flattening that corresponded to the zone of posterior elevation. The thinnest pachymetry was 196µm and the posterior surface showed localised elevation with an inferonasal island. Maximum elevation was 263µm over the best-fit sphere. Since refraction and topography remained stable over six months, Dr. Ferreira decided to implant a Sulcoflex toric lens in the left eye (653T 1.5 +3.0×119°). Postoperatively, the patient’s UDVA in the left eye was 20/50 and CDVA was 20/40 (+0.50 -0.50×35°), and the patient was very happy with the result.

The Q&A Session for the case studies included discussions about the ease of use of implanting the Sulcoflex as well as the benefits of no iris chafing or contact between the optics of the Sulcoflex and another implanted IOL. Prof. Amon highlighted rotational stability as point to be cautious about – since the lens is implanted in the sulcus, some rotation of the lens may occur. However, in cases where there is significant rotation, suturing the lens offers a straightforward solution.